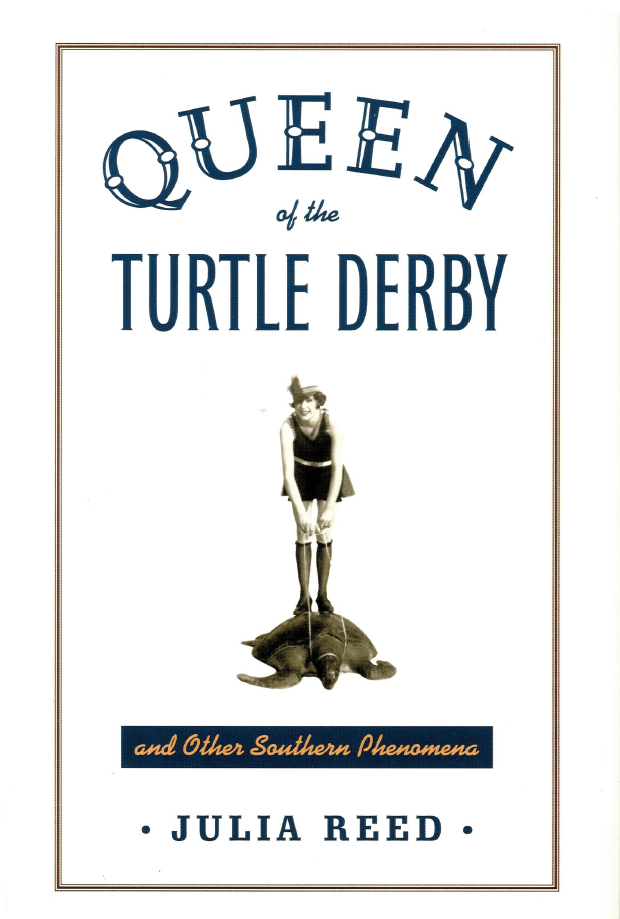

An excerpt from Queen of the Turtle Derby and Other Southern Phenomena by Julia Reed

An excerpt from Queen of the Turtle Derby and Other Southern Phenomena by Julia Reed

On Soggy Ground

In 1960, when I was born, Mississippi had then been dry for fifty-two years. This, to me, remains an astonishing fact, particularly since I didn’t learn it until 1972, six years after Prohibition had finally come to an end. 1 had always thought I was a pretty sophisticated kid—1 could have told you, for example, the names of Lyndon Johnson s dogs or of Richard Nixon’s entire cabinet. More to the point, I knew that a Gibson contained onions and a martini olives (or a twist) and that Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael had written “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening,” the song by which my mother invariably sang me to sleep. But, until a state law required me to take a Mississippi history course in the seventh grade, I did not know about another state law that was on the books until 1966: “No whiskey for any purpose whatsoever could be shipped into the State and no person could have, control, or possess any whiskey whatsoever.”

This seemed incredible. One of my earliest memories is of my father teaching me to make his martini, a service which I performed for years afterward and for which I was paid ten cents per drink. At five, my friend McGee began a larger enterprise when, frustrated by the slow sales at our neighborhood lemonade stand, she looked at her sister and me and asked, “Have you ever seen Mama or Daddy or any of their friends drink lemonade?” We had to agree that we had not. We had seen them drink old-fashioned and scotch sours, gin and tonics, Bloody Marys, and whole rafts full of cold beer in the summer, but we had never seen them drink much of anything else except for coffee and that was always early in the morning. McGee promptly pulled her wagon up to the vast refrigerator in her parents’ garage, unloaded the contents, and got rich selling cold Pabst Blue Ribbon for twenty cents a can to the many thirsty passersby on our country road.

No wonder I had never heard of the law, which itself was full of complications. The Mississippi state legislature, like those of several other Southern states, passed a statewide “bone dry law” in 1908, more than a decade before the federal government prohibited alcohol in the form of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution on January 16, 1919. Mississippi was the first state in the union to ratify the amendment, an act which moved the governor to give a speech about the good results of the law that Mississippi had already enjoyed. “The civil, economic, and moral life of our people has been greatly benefited by this law,” he said, adding that “sentiment is growing in favor of prohibition. It is true that we have a number of people who are breaking the law, either making or using liquor, but this does not meet the approval of the highest class of our citizens. . . . Our people practically unanimously will vote to make the whole world dry.”

He was right about the voting part at least. After the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment and officially ended federal prohibition on December 5, 1933, every other Southern state abandoned statewide prohibition except Mississippi, prompting the humorist Will Rogers to comment that Mississippians will continue to “vote dry as long as they can stagger to the polls.” (To this day the legislature has not formally ratified the Twenty-first Amendment.) However, by 1944, the number of people willing to risk the disapproval of “the highest class of citizens” by “making or using liquor” had grown sufficiently that the state decided to tax the sale of alcohol even though it was still illegal. This new law did not ever actually mention the word “liquor.” Rather, it called for a 10 percent sales tax on “tangible personal property, the sale of which is prohibited by law”—a bit of obfuscation that added up to $4-25 per case of whiskey, gin, etc., and seventy-five cents per gallon of wine.

By 1950, Mississippi had more retail liquor dealers, otherwise known as bootleggers, than any of the twenty-two legally wet states at the time, and more than twice the number in the two adjacent states of Tennessee and Arkansas combined. Furthermore, because booze was cheaper and more plentiful in Mississippi, the residents of Alabama and Georgia (both legally wet) drove over to buy their whiskey from us. In this free-flowing environment, law enforcement officers were generally well paid to look the other way, keeping up only halfhearted appearances for the sake of those few zealots among us. In 1952, for example, when my father’s friend J.B. came to visit him from Memphis, he thoughtfully brought along a case of gin as a house present. After a long night of drinking at a popular local “tonk” owned by Mr. Paul E. “Mink” Maucelli, one of our more prominent bootleggers, J.B. got lost trying to follow’ my father home and was arrested—not for driving drunk, though he was, but because a cop mistook him for a robber in the neighborhood. J.B. was released but the gin was not, a breach of hospitality that caused considerable local outrage. When my father confronted the police chief about it at the station the next day, the chief, with some sadness, explained that he had no choice: “It wasn’t just a bottle or two, Clarke, it was a whole case. A case. Why’d he have to drive around with a whole case in his car?” (At the cotton brokerage office next door, interest centered on the brand of the confiscated gin. “What kind was it?” asked one of the local characters, licking his lips. “Gordon’s or Gilbey’s?”)

In 1965, state records show’ that more than 450,000 cases of whiskey and 150,000 cases of wine were taxed, figures that don’t take into account the locally produced moonshine that constituted about 50 percent of the liquor market all through Prohibition. (It should be noted that the entire population of Mississippi is only two million.) Clearly, the people had found a way to live with the dry laws. As The Wall Street Journal noted six months before Prohibition was repealed, “Mississippi has arrived at a convenient and profitable arrangement with its conscience. The drys have their law, the wets have their liquor and the state has its taxes. Everybody’s happy.” During the annual liquor-bill debate in the state legislature in 1952, Representative N. S. “Soggy” Sweat crystallized his colleagues’ courageous stand on the issue in his famous “Whiskey Speech”: “You ask me how 1 feel about liquor. Here’s where I stand on this burning question. If when you say whiskey you mean the devil’s brew, the poison scourge that defiles innocence, dethrones reason, destroys the home, creates misery and poverty, yea literally takes the bread from the mouths of little children; if you mean that evil concoction that topples the Christian man and woman from the pinnacles of gracious living down into the bottomless pit of degradation and despair, then certainly I am against it. But… if when you say whiskey you mean the oil of conversation, the philosophic wine, the ale that is consumed when good fellows get together, that puts a song in their hearts and laughter on their lips, and the warm glow of contentment in their eyes; if you mean Christmas cheer; if you mean the drink that enables a man to magnify his joy and his happiness, and to forget, if only for a little while, life’s great tragedies, and heartaches, and sorrows; if you mean that drink which pours into our treasuries untold millions of dollars, which are used to provide tender care for our little crippled children, our blind, our deaf, our dumb, our pitiful aged and infirm; to build highways and hospitals and schools, then certainly I am for it. This is my stand. I will not retreat from it. I will not compromise.”

For a region that lives and dies by its time-honored, if tawdry, traditions and is known for its colorful, if not controversial, characters, the South has some explaining to do for its excessive eccentricities. And there is no one more capable than Reed, a Mississippi native and part-time resident of New Orleans and New York whose foot in both Dixie and Yankee camps gives her a unique, biregional vantage point from which to observe her homeland. Taking on such sacrosanct southern staples as cuisine, couture, and crime, Reed blends the factual with the fanciful to examine the ways in which southerners differ from their neighbors to the north. Going beyond the biscuits-versus-bagels bread brouhaha, Reed explores southern standards of beauty and exposes southern double standards of justice. She recounts the South’s penchant for pageants and fondness for football, shares its secret recipes, and skewers its salacious stereotypes in a playful collection of essays that humorously and humbly celebrates the quirkiness that lies deep in the heart of Dixie. Carol Haggas – Booklist