[Este artículo apareció en la edición de Marzo/Abril 2017 de la revista Zymurgy]

Por Amahl Turczyn

Varios escritores sobre cervezas han opinado acerca de las historias entrelazadas de las cervezas negras porter y stout. Algunos sostienen que la “stout” simplemente hacía referencia a cualquier cerveza fuerte; otros sugieren que es igual de posible que la stout haya existido como un estilo propio en paralelo con la porter ya desde fines del siglo XVII. En lo que los historiadores sí están de acuerdo es que Guinness fue fundada en Dublín por Arthur Guinness cuando alquiló una cervecería en St. James’s Gate, y que la empresa que fundó fue la responsable directa de que la dry stout haya llegado eventualmente a todo el mundo.

Varios factores contribuyeron al éxito de Guinness. Uno era la proximidad de la cervecería al Grand Canal de Dublín, que era perfecto para transportar barriles de cerveza y recibir suministros para fabricar cerveza. Los cereales cultivados en el centro de Irlanda también eran accesibles y fácilmente obtenibles. Otra ventaja era una fuente constante de excelente agua para cerveza, la cual en esa época también provenía del canal.

El mercado dio un giro favorable para la empresa en 1777. Guinness había estado produciendo porter para competir con la porter importada que se fabricaba en Londres, pero debido a los impuestos especiales existentes, los cerveceros de Dublín estaban sujetos a impuestos mucho mayores. En 1777, esos impuestos se levantaron y disminuyó la importación de porters londinenses, lo que le permitió a Guinness ver mayores ingresos y ampliar el negocio. A partir de entonces, la empresa pudo comenzar a exportar su propia porter, con cuentas en lugares tan distantes como las Indias Occidentales. Michael J. Lewis escribe en Stout que la cerveza exportada al Caribe en esa época fue probablemente el origen de lo que algún día sería la Guinness Foreign Extra Stout.

El último factor, y quizás el más importante, que contribuyó al éxito de la compañía fue la perspicacia comercial de sus fundadores. Una tradición de gestión inteligente y una visión de gran alcance para la expansión, iniciada por el fundador Arthur Guinness, fue retomada por tres de sus hijos después de su muerte en 1803. Para el año 1890, la cervecería de St. James’s Gate en Dublín era la más grande en su tipo y utilizaba equipos mecánicos sofisticados para fabricar cerveza a gran escala con el fin de responder a la demanda. Las exportaciones también aumentaron, y la stout de la cervecería llegó hasta el continente americano, África y Australia hacia fines del siglo XIX.

El término integración vertical es conocido por muchas empresas grandes, modernas y exitosas, incluyendo cervecerías como New Belgium y Oskar Blues, pero Guinness fue una de las primeras grandes fábricas de cerveza en utilizar la estrategia: tomar posesión de la cadena de suministro de materia prima para fabricar cerveza hasta llegar a ser propietarios de los pubs que vendían el producto terminado era prácticamente una garantía de éxito. No sería una sorpresa que la familia Guinness tuviera amigos en el gobierno que les garantizaran una legislación fiscal y comercial favorable en cuanto a la venta de cerveza.

Guinness evolucionó a través de muchas variaciones en su fórmula a lo largo de los años, a menudo dictada por los avances en el procesamiento de materiales. La malta black patent malt, un producto introducido por Daniel Wheeler en 1819, permitió a los fabricantes de cerveza dejar de utilizar la malta marrón y ámbar, y solamente usar malta clara con la nueva malta negra. Guinness reformuló lo que se convertiría en su ilustremente exportable Extra Stout utilizando black patent en 1821. Otra evolución tuvo lugar a principios de la década de 1930 cuando la cebada tostada más barata reemplazó la patent malt, y luego nuevamente en la década de 1950 cuando la empresa comenzó a utilizar una proporción de cebada triturada.

Stout de barril al estilo Dublín

Receta de Amahl Turczyn

- Volumen del batch: 20,82 litros (5,5 galones estadounidenses)

- Densidad inicial: 1,041 (10,3 grados Plato)

- Densidad final: 1,009 (2,3 grados Plato)

- Amargor: 43 IBU

- Color: 31 según el SRM

- Alcohol: 4,2 % según el volumen

MALTAS:

- 2,49 kg (5,5 lb) de malta clara británica

- 1,02 kg (2,25 lb) de cebada triturada

- 0,45 kg (1 lb) de cebada tostada británica de 500° L

LÚPULOS:

- 49 g (1,75 oz) de East Kent Goldings a los 60 min (30 IBU)

- 14 g (0,5 oz) de Challenger a los 60 min (15 IBU)

LEVADURA:

- Levadura Wyeast 1084 o White Labs WLP004 Irish ale (starter de 1 litro)

AGUA:

Agua de ósmosis inversa (OI) tratada con 0,5 g/l (2 g/gal) de sulfato de calcio

NOTAS DE FABRICACIÓN:

Macera la cebada clara y la triturada a 64° C (148° F) y déjala reposar durante una hora. Remoja la cebada tostada molida en un recipiente aparte con 2 L (2 qt) de agua a 68° C (155° F). Agrega agua caliente o hirviendo para aumentar la temperatura a 76 °C (168 °F) y deja reposar durante 10 minutos. Después de recircular el mosto para darle claridad, comienza a pasar al hervidor. En este punto, añade la cebada tostada junto con el agua de remojo al macerador y haz el lavado continuo a 80° C (176° F). Cuando la densidad del mosto se aproxime a 1,008 (2 grados Plato), detén el lavado. Si es necesario, cubre el hervidor con agua de ósmosis inversa. Hiérvelo durante 90 minutos y agrega el lúpulo a intervalos fijos. Enfríalo hasta 19° C (67° F) y oxigena. Agrega un fuerte starter de levadura y fermenta a 20 °C (68° F). Para maximizar la atenuación, asegúrate de que la densidad específica se haya estabilizado en 1,009 o (2,3 grados Plato) antes de transferir.

VERSIÓN DE MACERACIÓN PARCIAL:

Reduce la cebada triturada a 0,9 kg (2 lb) y la malta clara a 1,36 kg (3 lb). Macera todo junto a 66° C (150° F) durante una hora. Remoja la cebada tostada molida en un recipiente aparte con 2 L (2 qt) de agua a 68° C (155° F). Escurre y enjuaga los granos del remojo y macerado, y disuelve 0,9 kg (2 lb) de extracto de malta líquida clara dentro del mosto. Lava los granos a 80° C (176° F) hasta el volumen de hervor deseado con agua de OI, luego sigue como se indica arriba.

Si bien la marca de Guinness ha seguido siendo la más omnipresente de las Irish stouts, otros cerveceros irlandeses se destacaron en el mundo con este estilo. La fórmula actual de Guinness se basa en una gran proporción de cebada triturada sin maltear y cebada tostada, además de malta base clara, lo que produce una stout amarga y muy seca. Beamish y Murphy’s, ambas de Cork, tienen sus propias variaciones de este estilo.

Murphy’s utiliza una pequeña proporción de malta de chocolate además de malta tostada, con lúpulo Target en vez del énfasis de Guinness por el Goldings. La cerveza resultante es seca, pero no tan seca como el estándar de Dublín. Beamish reemplaza la cebada tostada enteramente a favor de la malta de chocolate y un poco de trigo malteado, y lúpulo Challenger, Goldings y Hersbrucker, para lograr una stout un poco más suave y cremosa. Desde la perspectiva de la elaboración de cerveza, hay que tener en cuenta que, al considerar la apariencia de la cerveza terminada, la malta de chocolate puede dar lugar a un color de espuma algo más oscuro que la cebada tostada, que produce una espuma casi blanca.

De las muchas variaciones, apuntaremos a una versión de barril de Dublín parecida a la Guinness. Veamos la materia prima, comenzando por el perfil del agua. Muchos estilos porter y stout requieren agua de elevada alcalinidad para equilibrar la acidez de los granos en el macerado. Sin embargo, para la stout seca, se prefiere un agua de baja alcalinidad y bajo contenido de minerales. Esto tiene que ver tanto con el proceso, en el cual la cebada tostada molida se remoja separada del macerado principal, como con el sabor ácido deseable que deriva del bajo pH de la cebada tostada. La nítida acidez final es una característica del perfil de sabor de la Dublin dry stout.

La fuente original de agua para la cervecería, al parecer, era muy suave y, de hecho, el experto en agua para cerveza Martin Brungard observa que la cervecería moderna utiliza la filtración por ósmosis inversa (OI) para mantener esta suavidad de las distintas fuentes de agua que se usan actualmente (ver: “Brewing Water Series: Ireland” de Brungard en la edición de Zymurgy de nov./dic. de 2012 para más información). Así que hay pocos motivos para tratar de reformular un perfil de agua de Dublín con sales minerales; el agua filtrada por OI debe ser suficiente o, si tu suministro local es bastante suave, eso debería andar bien.

La malta clara con alto poder diastático (como casi todas las maltas claras tienen actualmente) realmente es el único requisito para una dry stout. Es discutible si el sabor adicional y el carácter singular que se podría obtener al usar maltas Maris Otter, Optic, Pearl o Golden Promise se notaría en un estilo de gran amargor y sabor como este, si utilizáramos malta de origen británico exclusivamente en nombre de la autenticidad. Yo tiendo a preferir la malta clara domestica (americana) para la dry stout y he obtenido excelentes resultados.

La cebada tostada, sin embargo, es otro tema. Es posible que la cebada tostada domestica que está en el rango de 300° a 400° L no logre el color negro “adecuado” de 30 según el SRM. (El BJCP permite un rango de color de 25 a 40 según el SRM para este estilo). Busca una tostada de 500° L de gran calidad, específica para dry stout, a veces llamada “cebada negra” o “cebada stout”. En general suelo optar por una marca británica, pero las malteras de EE. UU. como Briess también fabrican una excelente cebada negra con el requisito de color de 500° L.

Se puede hacer una dry stout muy buena con lúpulo cultivado en EE. UU., pero como este estilo se basa muchísimo en la presencia del lúpulo, pienso que lo mejor sería optar por Target, Challenger, Goldings o una combinación de los tres, aunque en la receta solo se requieren adiciones tempranas. Se dice que Guinness agrega una pequeña cantidad de extracto de lúpulo a su cerveza terminada, así que tal vez haya una nota de lúpulo distintiva escondida en el aroma complejo de la cerveza.

La levadura para cerveza irlandesa es limpia y atenuante, pero puede agregar unos ésteres frutales a altas temperaturas. El bien documentado cronograma de fermentación de Guinness comienza a 17° C (63° F), pero luego se deja aumentar hasta 23 a 27° C (74 a 80° F), para garantizar una rápida fermentación de tres a cuatro días. Esto tiene sentido para una producción de gran volumen y alta rotación, pero a los cerveceros caseros, les advierto que el sabor frutal puede irse de las manos por encima de los 23° C (74° F). La mayoría de los laboratorios de levadura recomiendan no más de 22° C (72° F) para la cepa. Anecdóticamente, he descubierto que la cepa actúa fuerte y limpiamente a 20° C (68° F), así que eso es lo que recomiendo.

Para el macerado, son deseables las temperaturas que producirán un mosto altamente fermentable. Un macerado de 70 minutos a 64° C (148° F) era el procedimiento estándar en Guinness según Lewis, seguido de un aumento de temperatura y lavado a 80° C (176° F). Para nuestra receta, especialmente si usamos malta con mayor poder diastático, 60 minutos son suficientes, pero igual se recomienda el lavado a alta temperatura, ya que el alto porcentaje de cebada triturada puede volver gomoso el macerado con beta-glucanos. (Si tu sistema de fabricación de cerveza es propenso a que se atasque el macerado, lo mejor es tener unas cáscaras de arroz a mano por si acaso). Remojar la cebada tostada finamente molida por separado del macerado principal de malta clara y cebada triturada evita que el pH se vuelva demasiado bajo durante la conversión del almidón. Eso no quiere decir que no se pueda hacer una dry stout decente simplemente macerando todo junto, pero el remojo por separado produce un resultado final notablemente más suave y más integrado.

Agregar los granos tostados y el agua de infusión después de una hora de la conversión hará bajar el pH del macerado durante el lavado, pero para entonces la mayor parte de la acción enzimática habrá cesado, y el lavado simplemente servirá para enjuagar el sabor restante del tostado. Curiosamente, Lewis observa que la cervecería Park Royal Guinness con sede en Londres y la cervecería original St. James’s Gate de Dublín tenían procedimientos de macerado diferentes: en un punto Park Royal maceraba al menos una parte del grano tostado junto con la malta clara y la cebada triturada; St. James’s Gate utilizaba un remojo separado para el tostado ¡y agregaba el extracto resultante al mosto claro en el hervidor!

Uno pensaría que desde entonces se habrían aplicado estándares modernos sobre la consistencia del producto para encontrar algún tipo de consenso entre los procedimientos de ambos lugares, pero al agregar la cebada tostada más tarde en el macerado, estamos en algún punto entre los dos procedimientos. Para llevar el procedimiento de remojo al extremo, incluso se podría hacer un remojo en frío del tostado molido un par de días antes y luego agregar el extracto tostado después del hervor para un resultado aún más suave; este es un método común para usar café tostado en la cerveza, aunque esta sugerencia para la stout es puramente teórica.

Al envasar la dry stout, personalmente creo que guardar en barril es mejor que el embotellado, pero, sin duda, haz lo que puedas con los recursos que tengas. Guinness, y de hecho todas las dry stout, se han vuelto conocidas por el famoso “nitro pour” (mezcla de nitrógeno) mediante el cual una cerveza terminada con un carbonatado relativamente bajo es forzada a través de una placa perforada al momento de dispensar, produciendo cascadas de burbujas diminutas que suben a la superficie en forma de una rica capa de espuma fina y cremosa que con frecuencia dura hasta el fondo del vaso. Obviamente, un sistema dedicado de barril de nitrógeno, incluyendo la mezcla apropiada de gases y el grifo de la placa reductora, es la mejor manera de lograr este resultado hermoso y fácil de beber en el vaso, pero con un poco de práctica, hasta los cerveceros caseros que usan barriles Cornelius y con tapa cobra podrán lograr una buena aproximación.

Al carbonatar la stout hasta aproximadamente 4 gramos por litro (2 volúmenes) de CO2 y aplicar una presión superior (usando CO2 normal) de 172 a 207 kPa (25 a 30 libras por pulgada cuadrada), se puede utilizar el dispensador con tapa cobra como punto de restricción. Como cerveceros caseros, estamos acostumbrados a dispensar con el grifo completamente abierto para lograr un vaso de cerveza carbonatada relativamente libre de espuma. Pero simplemente apretando apenas la manija para forzar la stout a través de una abertura estrecha a alta presión, se puede imitar el vertido en cascada de la Irish stout. Si la carbonatación de la cerveza es demasiado alta, este método dará como resultado un vaso de espuma; si es demasiado bajo, no obtendrás casi nada de espuma (de tu cerveza sin gas). Pero si logras el equilibrio correcto ¡te sorprenderá el buen sabor y gusto de esa pinta de stout casera! Ah, y no te olvides de reducir la presión superior en el barril después de que termines de servir las pintas, de lo contrario carbonatarás de más la cerveza. Y entonces será pura espuma de todas formas. ¡Sláinte!

* * *

Amahl Turczyn es subredactor de Zymurgy.

Recursos:

- Lewis, Michael J. Classic Beer Style Series: Stout. Brewers Publications, 1995.

- Jackson, Michael. Michael Jackson’s Beer Companion, Duncan Baird Publishers, 1993.

- Kemp, Florian. “The Evolution of Dry Stout,” All About Beer, 35, Edición 6, 17 de marzo de 2015.

The post Enfoque en ciertos tipos de cerveza: Dry Irish Stout appeared first on American Homebrewers Association.

48 quart picnic cooler

48 quart picnic cooler

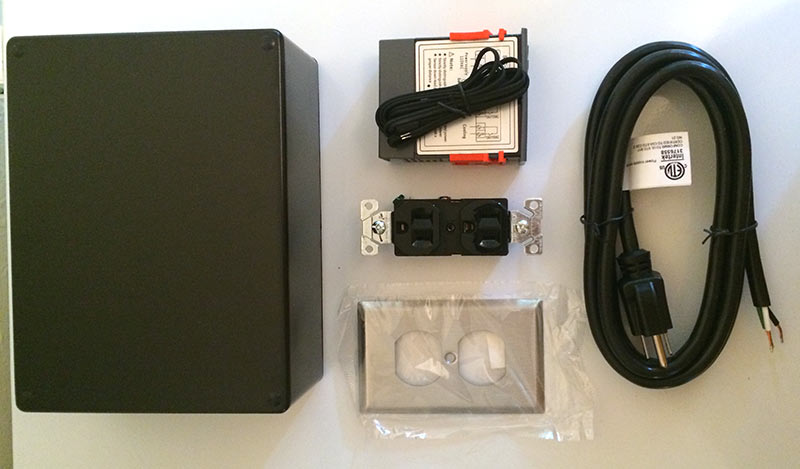

Unpackage the project box, STC-1000 and wall outlet. Place the STC-1000 and power outlet where you want them on the box and trace with a pencil. Cut along the outline with the dremel. It may take a few rounds to get the fit just right. Test to make sure the STC-1000 (remove the orange tabs, they will be used later) and wall outlet fit snuggly into the holes cut in the project box. You will also want to cut a hole for the power cable and temperature probe to run out, and the location will depend on how you plan to mount the temperature controller. I cut mine at the bottom side of the project box so the wires would be aiming down when the temperature controller is mounted to the wall.

Unpackage the project box, STC-1000 and wall outlet. Place the STC-1000 and power outlet where you want them on the box and trace with a pencil. Cut along the outline with the dremel. It may take a few rounds to get the fit just right. Test to make sure the STC-1000 (remove the orange tabs, they will be used later) and wall outlet fit snuggly into the holes cut in the project box. You will also want to cut a hole for the power cable and temperature probe to run out, and the location will depend on how you plan to mount the temperature controller. I cut mine at the bottom side of the project box so the wires would be aiming down when the temperature controller is mounted to the wall. Prepare the wires. For this build you will need eight 5-inch pieces of wire. Cut off a piece of the power cord and strip to reveal the internal wires. To keep things from getting too confusing, plan to cut three pieces of black wire, four pieces of white wire and one piece of green wire. The green wire is used for grounding and is not supposed to be used for anything other than the ground, so we recommend you do not use these for any of the hardwiring besides tying the outlet’s ground to the power cord’s ground. On either end of the wire segments, strip a half-inch of the insulation to reveal the inner wires.

Prepare the wires. For this build you will need eight 5-inch pieces of wire. Cut off a piece of the power cord and strip to reveal the internal wires. To keep things from getting too confusing, plan to cut three pieces of black wire, four pieces of white wire and one piece of green wire. The green wire is used for grounding and is not supposed to be used for anything other than the ground, so we recommend you do not use these for any of the hardwiring besides tying the outlet’s ground to the power cord’s ground. On either end of the wire segments, strip a half-inch of the insulation to reveal the inner wires.