So you want to brew a fruit beer. You’ve selected the perfect base beer style and fruit combination and it’s time to start sourcing the fruit and making a plan of attack.

As with many aspects of homebrewing, there are many ways to achieve a similar outcome, so think about which of the following processes will work best when planning to add fruit to beer.

Finding Fruit

Finding the fruit for your beer is as simple as heading down to the grocery store and loading up the cart, right? To some extent, yes, but a beer can only be as great as its raw ingredients, so it is crucial to try and find the highest quality produce you can get your hands on.

In a perfect world, fruit is grown in your backyard. Buy growing your own, you can allow the fruit to achieve optimal ripeness, and you know the exact what conditions the fruit was grown in. But, alas, growing fruit trees is not something you wake up and decide to and have ready for your next brew day. Off to the market…

Before heading to the grocery store, look for local farms and nurseries or visit your neighborhood farmers market. These sources produce the “heirloom” type of produce that typically use minimal amounts of chemical growers and pesticides and focusing on quality product rather than speedy mass production. This option may be a bit pricier than going to the store, but the quality is worth the expense to achieve delicious fruit flavor in your beer.

And if all else fails, head to the grocery store! Great fruit beers can still be made with produce purchased from grocery chains, with a little extra care. First, spend some time rummaging the fruit bins for the ripest specimens you can find. Mass producers of fruits often harvest before the point of optimal ripeness to extend shipping and shelf life. The trade off is a less-flavorful fruit. Grocery store fruits are also often grown and treated with chemicals, so take care to give fruit a thorough washing before adding to a beer (though, this should be done with any produce purchased).

If fresh fruit is not available, frozen fruit and purees are the next best option. Frozen fruit and purees are also a great way to purchase quality fruit ingredients at a more affordable cost, especially if your recipe calls for large additions. They also take less time to prepare when adding to beer. Keep an eye on the ingredients and avoid products that have large amounts of preservatives.

Juices are another option that can be used with great success, and like frozen fruits and purees, you should look for products free of preservatives and made of real fruit. Some folks use extracts and essences of fruits, but this is where you start to get into the realm of the artificial-tasting fruit beers.

Fruit Amounts

With a source of fruit determined, you now need to know how much fruit to purchase. This is not a cut-and-dry situation, and since fruit beers are created from many different base styles, you need to focus on balancing the strength and qualities of the beer with that of the fruit.

For example, two pounds of raspberries may be perfect in your five-gallons of strong stout, but the same amount in a session wheat beer could be overwhelmed with raspberry character. Also, take into account whether or not the fruit has a strong acidic quality, which will require more consideration in creating balance between the fruit and base beer.

Be sure to keep careful notes of the amounts you use in relation to your batch size and recipe, so in the future you can make more informed decisions based on your experiences and your preferred taste. The following chart can be used as a starting point to determine the appropriate fruit amounts in any given homebrew recipe:

| Fruit (fresh) | Pounds/Gallon | Grams/Liter |

| Apricots | 0.25 – 2.0 | 30 – 240 |

| Blackberries | 0.5 – 4.0 | 60 – 480 |

| Blueberries | 0.5 – 3.0 | 60 – 360 |

| Cherries (sour) | o.25 – 2.0 | 30 – 240 |

| Cherries (sweet) | 0.33 – 4.0 | 40 – 480 |

| Citrus | 0.25 – 1.0 | 30 – 120 |

| Currants | 0.33 – 1.5 | 40 – 180 |

| Peaches | 0.5 – 5.0 | 60 – 600 |

| Plums | 0.5 – 2.0 | 60 – 240 |

| Raspberries | 0.25 – 2.0 | 30 – 240 |

| Strawberries | 0.5 – 3.0 | 60 – 360 |

This table was taken from “Sweet & Sour: Adding Fruit to Sour Beer” by Kevin Wright featured in the May/June 2015 Zymurgy magazine. Access the article and see the full chart which includes equivalents for purees, concentrates and dehydrated/dried fruits.

Preparing & Adding Fruit

The methods of preparing fruit will largely depend on the form of the fruit (ex. whole, puree, juice, etc.), and at what point the fruit will be added to the beer. Again, there are many ways to skin the proverbial cat.

Whole, puree and juiced fruit is often added in the last minutes of the boil. This acts as a quick pasteurization step to prevent any potential bacterial contamination that could make your fruit beer go south. Adding fruit to the boil means the fruit is in the wort during active fermentation. Having fruit in the fermenter during fermentation causes a much different fruit character then you might find when adding fruit post-fermentation.

For starters, the fruit will likely add fermentable sugars to the wort, which you may want to account for when formulating the recipe. Fermented fruit also has a much different character then post-fermentation fruit additions. A lot of the fruit character will be blown off from the rigor of fermentation, and what remains will be a more wine-like fruit character since the fruit’s sugars were fermented, rather than a fresh fruit quality. In some fruit beers, especially those that may use wine grapes, the fermented fruit character may be desired.

Purees and juices can be added directly to the boil kettle. You can do the same with whole fruit, but you may want to consider mashing or pulse-blending the fruit before adding it to the boil to help release more of the juices. Bagging the fruit in a hop bag is suggested if dealing with a lot of flesh and seeds, but it’s not 100 percent necessary if you take care not to rack the solids into the primary fermenter.

If you’re after more fresh fruit character that is reminsicent of the raw fruit being used, then stick with post-fermentation additions after primary fermentation has nearly completed. However, since you don’t have the high temperatures as you would when boiling fruit, you need to take extra care to avoid contamination (unless, of course, you are after something wild). Often times juices, purees and frozen fruits undergo flash-pasteurization which leaves little risk for contamimation if added to beer. Whole fruit, on the other hand, is another story.

First, mash or pulse-blend the fruit to release the juices and create more surface area for the beer to be in contact with the fruit. Now you have three options for pasteurization. First, is a low-heat pasteurization method that you can do in a double boiler or carefully directly on heat. Hold the mashed fruit at around 150-170°F for about 15 minutes, and that should rid the fruit of most of the unwanted bacteria. Second, simply freezing the mashed fruit before adding it to the fermenter. It is said that freezing and thawing fruit a few times helps release more flavors by breaking down cell walls, which means a fruitier brew! Third, simply do nothing at all and hoping for the best (good luck!).

Once you’ve pasteurized your mashed fruit, bag it in a hop bag like you would dry hops and add it to your secondary fermenter or keg. Make sure all the juices make it into the fermenter, too, even if the bag doesn’t contain it. Then, simply age it on the fruit like you would dry hops. Pull samples and once it tastes as you hoped, yank the bag and bottle or start serving! You can forgo the hop bags and add fruit directly to the fermenter, but this will likely require filtering, racking to additional fermenters and/or cold crashing to get clear, solid-free fruit beer.

Sources: “Brewing with Fruit” by Dave Mentus (May/June 2010 Zymurgy); “Notes from a Fruit Beer Fancier” by Randy Mosher (July/August 2002 Zymurgy); “Sweet & Sour: Adding Fruit to Sour Beer” by Kevin Wright (May/June 2015 Zymurgy).

The post How to Add Fruit to Beer appeared first on American Homebrewers Association.

At this point, you should pick your hops into sacks and weigh them. It is always more fun to have a helper. Place a single variety into a single (screened) tray. Once your tray is full (about 1/3 up the side), set it on top of the base tray over the fan so that the tray edges align perfectly over each other. Continue to pick your hops, fill your trays and stack them up. Leave one of the trays empty to the side. I used a piece of masking tape to mark each tray to know which variety was in which tray. Next year, I may just add a plastic sleeve to the side and make up cards with the names of the varieties I grow to sort them that way (it will look much nicer).

At this point, you should pick your hops into sacks and weigh them. It is always more fun to have a helper. Place a single variety into a single (screened) tray. Once your tray is full (about 1/3 up the side), set it on top of the base tray over the fan so that the tray edges align perfectly over each other. Continue to pick your hops, fill your trays and stack them up. Leave one of the trays empty to the side. I used a piece of masking tape to mark each tray to know which variety was in which tray. Next year, I may just add a plastic sleeve to the side and make up cards with the names of the varieties I grow to sort them that way (it will look much nicer).

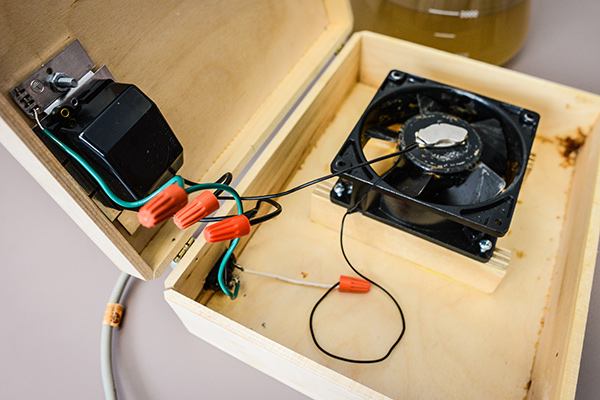

Start by centering the fan inside the box you selected. Secure the fan to the base using screws or super glue, taking care not to hinder the movement of the fan.

Start by centering the fan inside the box you selected. Secure the fan to the base using screws or super glue, taking care not to hinder the movement of the fan. Drill small holes through the box to secure the on/off switch. Do the same if using a rheostat.

Drill small holes through the box to secure the on/off switch. Do the same if using a rheostat. Once the stir plate is functioning with the ability to control the speed of the fan, seal/close the box containing the electrical components. As a test, fill the flat-bottomed starter vessel to a typical volume you will be working with and gently add the magnetic stir bar.

Once the stir plate is functioning with the ability to control the speed of the fan, seal/close the box containing the electrical components. As a test, fill the flat-bottomed starter vessel to a typical volume you will be working with and gently add the magnetic stir bar.

Harvesting Your Hops

Harvesting Your Hops

Package Your Hops

Package Your Hops