There is no doubt that the explosion in popularity of IPA has changed the landscape for craft beer producers and consumers, as well as homebrewers. Between the evolution of the style to fit the wants of the drinking public, the many stylistic offshoots of IPA that have become commonly available, and the increasing quality of flavor and aromatics that many brewers seem to be achieving, it is no wonder that exploration of ingredients and techniques for brewing IPA is at an all-time high.

Many of the best IPAs are made with generous additions of hops both late in the boil and post-boil, or in the whirlpool. There is even a technique that has spawned off of this thinking called hop bursting, where massive additions of flavor and aroma hops are used to obtain bitterness, in addition to huge amounts of hop character in both flavor and aromatics.

Mitch Steele, formerly of Stone Brewing Company, has been one of the foremost experts on this technique, and has discussed it in numerous forums, including his book, IPA: Brewing Techniques, Recipes and the Evolution of India Pale Ale, presentations at the National Homebrewers Conference and in an article in the November/December 2013 edition of Zymurgy magazine. In that article, in reference to whirlpool hop additions, Steele stated, “Many brewers neglect to consider the bitterness obtained from this addition, but it can be substantial, depending on the volume of hops added.”1

When reviewing the means in which many homebrewers measure the bitterness in their beers, the bitterness obtained from a post-boil/whirlpool hop addition is often not considered, in part due to the available means for calculating estimated IBUs. While there are multiple ways to estimate the IBUs in a finished beer, the Tinseth and Rager formulas are the most widely used. The Rager formula, which was introduced in Zymurgy magazine in 1990, does give a 5% utilization yield to hops added post-boil. The Tinseth formula on the other hand, gives no IBU contribution for a post-boil hop addition.2

After trying to brew a beer where I only added whirlpool hops and getting an ample amount of bitterness from that addition, I began to ask the question, “just how much utilization is obtained from post-boil additions, and how does the amount of time at certain temperatures affect that?” There are many real world examples of IPAs that use a whirlpool addition to obtain most of their bitterness. Adam Mills, the head brewer at Crankers Brewery in Big Rapids, MI detailed in a presentation at the 2014 National Homebrewers Conference how he obtains essentially all of the 65 IBUs in their Professor IPA from whirlpool additions3, and beers such as Stone’s Enjoy By Double IPAs are documented as relying significantly on a whirlpool addition for bitterness

Experiment Overview

Based on the questions posed above, the conducted experiment aimed to measure the effect of different post-boil hopping techniques and their effect on calculated and perceived bitterness, as well as hop aroma and flavor.

The experiment began with a series of 10 different batches with the same wort being made in roughly 1 gallon quantities, using carefully measured and consistent ingredients, each utilizing a different post-boil hopping technique, with variances on time and temperature being the only intended independent variables. The finished beers were fermented in the same size containers, using the same yeast, and in the same location. After fermentation was complete and the beers were bottled, they were sent to the Bell’s Brewery analytical lab, where they were tested for measured IBUs. In addition, the beers were served to a tasting panel made up of a group of “super tasters” from Bell’s Brewery, and included a collection of BJCP judges, certified Cicerones, and others with significant levels of sensory training and tasting experience. These tasters took a sample of the beers which were made, and rated them on the basis of hop bitterness, aroma and flavor.

As mentioned, the ingredients were chosen primarily to ensure the beers were as consistent as possible, not necessarily because they would make the best beer for drinking. The base chosen included the following ingredients:

- Water – Distilled Water was used as a base with both 0.3g of gypsum and calcium chloride added to give the beer an appropriate level of calcium content. Exactly 1 gallon of water was used for each batch.

- Malt – With consistency in mind, a wort with 95% Briess Pilsen DME, and 5% dextrose sugar was decided upon. The use of malt extract allowed for the ability to ensure each batch had the same wort composition, and made the project feasible from a time standpoint. The starting OG of each wort was 1.057 (14 Plato).

- Hops – Exactly 1 ounce of hop pellets (measured with a precision gram scale) were added to each batch in a single addition. The desire was to use a high-alpha dual-purpose hop was that would provide an ample amount of bitterness, but also lend a profile one would expect from a hoppy Pale Ale or IPA. In this experiment, the choice was to use El Dorado hops packed in 1 ounce bags from BSG. The hops had a listed Alpha Acid content of 14.9%.

- Yeast –Safale US-05 dry yeast was used for fermentation. While there is a great deal of evidence that rehydration of dry yeast is best practice, exactly 3 grams of yeast was pitched directly into each fermenter to ensure each beer got the same amount of yeast.

As noted, the goal of consistency was not just limited to ingredients, but the process was intended to ensure this as well. The process of brewing and fermenting the beers was as follows:

- Boil – The DME was boiled for 15 minutes, on a stovetop. To ensure an even boil off rate, the exact same heat intensity from the burner was used in each beer.

- Hop additions – Hops were added during different intervals based on which batch was being brewed. Hop pellets were added loose into the wort. As noted earlier, 1oz of hops were added to a batch that was approximately 1 gallon in size. Scaled up, this translates to an addition of approximately 1.9–2.0lbs/bbl.

- Hop Stand – This was one of the variables that changed in each batch. Further discussion will follow on how the hop stand for each batch was treated.

- Chilling – Chilling was conducted using a 20’ piece of ¼” ID copper coil fabricated into an immersion chiller. Groundwater from a kitchen faucet, with a temperature of 64° F, was used for chilling.

- Wort Transfer – The wort was transferred into the 1 gallon glass fermenters by dumping the wort in using a funnel. Since each batch was left to settle out for roughly 30 minutes following cooling, the majority of the trub was left in the kettle. This left total yield of roughly 0.8 gallons for each batch.

- Yeast Pitching – As noted, 3 grams of yeast was pitched dry into each fermenter. The amount being pitch was weighed by setting the packet of yeast on a gram scale (after thorough sanitizing using Star-San), and slowly added in steps until 3 grams were pitched.

- Aeration – The wort in each fermenter was aerated by vigorous shaking for 1 minute.

- Fermentation – Each batch was fermented concurrently in a basement, in Michigan, during August 2015. Due to a heat wave late in the month that saw outside temperatures reach over 90° F, the fermentation area was warmer than normal, and actual wort temperatures during the bulk of fermentation (as measured by a temperature controller, with the probe taped to the side of one of the glass carboys under insulation) was conducted between 69°–72.5° F, which is on the warmer end of the recommended temperature range for the strain.

- Bottling – Following a 3 week fermentation, the batches were racked into a bottling bucket using a mini-auto siphon. 17 grams of dextrose was added, mixed in with the beer, and bottled for natural carbonation. The bottles were conditioned at room temperature, around 68°–72° F.

Because of the small batch nature of the experiment, equipment had to be customized to fit the process and ingredients being used. Primary pieces of equipment used were:

- Boil Kettle – A pair of 6 quart stainless steel kettles were used for brewing the 10 small batches.

- Burner – A natural gas stovetop burner was used for boiling the wort.

- Hop stand heat source – A small stove top burner (smaller than used to boil) on its lowest setting was used to hold temperature during the hop stand portion of the batches in the experiment in Set 1, as detailed below.

- Range Supermechanical thermometer – The Range Supermechanical Thermometer, a smart thermometer that connects with iOS devices and includes the ability to export temperature data, was a key piece of this experiment, and allowed the temperatures in the kettle to be measured while the wort was in contact with the hops. Following each of the 10 batches, the data recorded was exported for further analysis.

- Funnel – Used to aid in the wort transfer.

- Fermenter – Fermentation was conducted in a 1 gallon glass carboy with a plastic screw-on lid with a hole designed for an airlock.

- Bottling – Standard 12oz bottles were used for the finished beer, bottled using a standard 6 gallon bottling bucket.

Specific Analytical Measurements

The primary information measured in the experiment were the variables of temperature and bitterness, measured in International Bittering Units (IBUs). Along with IBUs, other data was used to calculate an estimated utilization for each batch. The method for measuring each of these variables is as follows:

- Temperature – The temperature was measured using a Range Supermechanical smart thermometer, which works with any iOS device. The thermometer is capable of measuring to a tenth of a degree Fahrenheit, and can log temperature data up to one reading per second. This data, which was recorded for each batch, was used to determine average actual temperature of each hop stand.

- International Bittering Units (IBUs) – The IBU measurements were made with the assistance of the lab at Bell’s Brewery in Comstock, MI. Bell’s used the ASBC Beer-23A method of measuring IBUs, which is a test where the beer is chilled and centrifuged, then dosed with isooctane, a compound which absorbs bittering compounds, including, but not limited to, isohumulones, hulupones and humulinones. This solution is then tested for the amount of light that is absorbed at 275nm, with the amount of absorption determining the level of bitterness in the sample.4

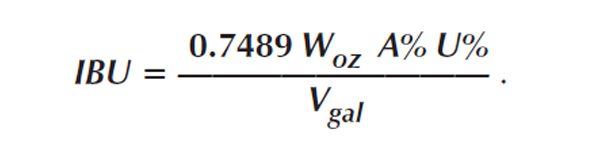

- Utilization – The utilization estimate was calculated using the equation below, as published in Zymurgy’s special edition, “The Classic Guide to Hops.”2 Since the IBUs were known via testing, the utilization percentage was calculated using the other known variables.

The other variables used to solve the equation included:

- Woz = 1

- A% = 14.9%

- Vgal = 1.0

The results of these measurements are included in the below charts summarizing the collected data.

Sensory Approach

For the sensory portion of the experiment, a panel of eight tasters from Bell’s Brewery tasted beers in two sets, which included two beers from Set 1, and three beers from Set 2. For each set, the tasters were asked to rate which beer had the most and least aroma, flavor and bitterness. The results are discussed in further detail below.

Comparison of Batches

The experiment was conducted with batches split into two sets. The goal of the first set was to test the effect of temperature on bitterness, with the goal of the second set being to test the effect of contact time on bitterness.

Set 1 – Effect of temperature on bitterness of post-boil hop additions

In Set 1, which included four batches, the effect of the temperature of the wort was tested to determine what, if any, effect it had on the bitterness imparted in the beer. For this set, a 30 minute hop stand was conducted at temperatures ranging from 180°–210° F. After 30 minutes the batches were immediately cooled using an immersion chiller. The temperatures were maintained by using direct heat to the kettle, in the form of a small burner on a gas stovetop, using the lowest setting. The temperature was monitored manually based on the reading from the Range Thermometer, which was submerged in the center of the kettle. When the temperature dropped a degree below the target temperature, heat was applied until it reached the target temperature. The results of the lab analysis completed on each of these batches is listed below.

| Batch | Description | Avg. Temp. during hop stand | Lab Tested IBUs | Estimated Utilization (%) |

| #1 | 30 Minute Hop stand held @ 210° F | 210.0° F | 48.6 | 4.36 |

| #2 | 30 Minute Hop stand held @ 200° F | 199.6° F | 57.2 | 5.13 |

| #3 | 30 Minute Hop stand held @ 190° F | 189.7° F | 50.7 | 4.54 |

| #4 | 30 Minute Hop stand held @ 180° F | 179.9° F | 44.2 | 3.96 |

The most notable observation from the temperature data is the fact that it doesn’t follow a downward trajectory in a linear or exponential fashion. Based on what we know about the isomerization of alpha acids, heat does play a factor, and isomerization does increase with temperature. The anticipated result was that the IBUs in the finished beer would decrease as the temperature decreased, however, to what extent they would decrease was unknown.

What the results suggest, in which the IBUs actually increased in the 200° F and 190° F batches compared to the 210F batch, is that a variable in the equation created inconsistent results that do render this set of data somewhat inconclusive. While it’s impossible to pinpoint the exact reason for the variances, the one variable that certainly was different batch to batch was the level of heat applied to the kettle to maintain temperature. Because the wort was not moving except for a short manual whirlpool after the hops were added, and potentially because of the small batch size, it is possible that the temperature in the kettle may have varied from the center, where the temperature probe was measuring, to the sides of the pot, and especially near the bottom, where the kettle may have been materially hotter due to the direct heat being applied. This merits a reevaluation of technique, which is discussed in greater detail in the conclusion.

Set 1 – Sensory Results

For Set 1, the two beers which had the highest temperature and lowest temperature hop stand were chosen for evaluation. Despite the 30° F difference in temperature, the sensory evaluation was highly inconclusive. This could be partly due to the fact that the bitterness levels were so similar, and doesn’t answer the question whether aroma and flavor compounds are retained more effectively at higher temperatures.

| Batch | Most Aroma | Least Aroma | Most Flavor | Least Flavor | Most Bitterness | Least Bitterness | ||

| The numbers above represent how the eight tasters voted on specific elements of the beers that were ranked. | ||||||||

| #1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||

| #4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | ||

Set 2 – Effect of time on bitterness of post-boil hop additions

In Set 2, the focus shifted from testing the temperature of a hop stand, to testing how the amount of time would affect the level of bitterness imparted into the beer. For this set, 6 beers were brewed, with varying lengths conducted for the hop stand. One of the beers got no hop stand, but instead had an addition that was boiled for 10 minutes, to form a baseline to compare against for the beers which had hops added post-boil.

For this set, no heat was applied to the kettle during the hop stand. However, to limit the thermal loss of the small 6 quart kettle being used, the pot was placed into a larger, 5 gallon pot filled with near boiling water immediately following the boil, and allowed to rest untouched until the immersion chiller was used to cool (for batches 7 – 10).

| Batch | Description | Avg. Temp. during hop stand | Lab Tested IBUs | Utilization (%) |

| *Although Batch #6 did not receive a hop stand, the hops were still in contact with hot wort for a short period of time. The temperature of the wort exceeded 200° F for 38 seconds, exceeded 180° F for an additional 24 seconds (62 seconds total), and dropped to 160° F 30 seconds later (92 seconds total) | ||||

| #5 | Hops Boiled for 10 Minutes | N/A | 48.1 | 4.31 |

| #6 | Flameout addition, immediate chill | N/A* | 28.9 | 2.59 |

| #7 | Flameout addition, 10 min. hop stand | 205.5° F | 39.9 | 3.58 |

| #8 | Flameout addition, 20 min. hop stand | 204.6° F | 44.1 | 3.95 |

| #9 | Flameout addition, 30 min. hop stand | 201.7° F | 50.0 | 4.48 |

| #10 | Flameout addition, 60 min. hop stand | 193.7° F | 56.4 | 5.05 |

Unlike Set 1, Set 2 did display a pattern that seems in line with the direction that would be expected for IBU levels between the different batches. The 10 minute boil still produced a significant amount of IBUs, and while the 10 and 20 minute hop stands were lower in measured bitterness, the IBU contribution was still significant. By 30 minutes, IBUs had increased over the 10 minute boil batch, and in the batch which received a 60 minute hop stand, IBUs rose even higher.

As the hop stands got longer, it does appear that there were diminishing returns on bitterness extraction, especially past the 10 minute mark. With an increase of 4 IBUs from the 10 to 20 minute batch, 6 more from 20 to 30 and another 6 from 30 to 60 minutes, some combination of reduced temperature and the availability of alpha acids that were still available to be isomerized may have been factors that created a leveling off in the amount of bittering that could be generated over time. This is reminiscent of the same effect when hops are boiled for longer periods of time, such as comparing IBUs in a 60 minute boil versus a 90 minute boil.

One interesting takeaway was the level of IBUs that were generated in Batch #6, which had hops added but then was chilled immediately with the immersion chiller. While there was no hop stand on this batch, the hops were still in contact with hot wort for a short period of time, though the temperature was below 160° F within 92 second of the hops being added. Despite this short contact time with hot wort, 29 IBUs were still created, which suggests that maybe isomerization of the alpha acids occurs very quickly. The other possibility is that compounds other than iso-alpha acids are creating bitterness. This possibility is discussed further in the conclusion. In either scenario, more investigation would be needed to come to any conclusions.

With some assumptions, a theoretical utilization curve can be created using the data from Set 2 (See Figure 1). It is important to note however this curve does make some assumptions about each hop stand batch and that the temperature was constant over time for each. While not perfect, the average temperature data shown in the Addendum to this report does show consistency over 10 minute intervals within no more than 1-2 degrees difference in average temperature over similar time periods. It is also important to understand this chart is a visual representation of the data collected in the experiment, and should not be relied upon as a predictable indicator of hop utilization for post-boil additions. When the data is visualized, it does imply that bitterness is imparted very quickly, and levels off quickly as well, but still increases all the way to the 60 minute mark. This is an interesting observation, however more testing would be needed to validate and explore the speed of isomerization, or the extraction of other bittering compounds, in regards to very short versus long hop stand rests. An additional question this raises is if a brewer wants to obtain some bitterness at flameout, is it possible to get the quick hit of bitterness as seen in Batch #6, then very quickly chill to retain the volatile essential oils from the hops? There are certainly multiple schools of thought on this. For instance, award-winning homebrewer turned award-winning craft brewer Jamil Zainasheff writes on his webpage Mrmalty.com that “Sitting at near boiling will continue to isomerize the hop acids and drive off the volatile oils that good hop aroma and flavor depend upon.” 5 If significant amounts of bittering are generated very quickly, would this technique be favored? Again, more research would be needed to draw any conclusions.

Figure 1 – Utilization % by time of hop stand (in minutes)

Set 2 – Sensory Results

For Set 2, three beers were chosen for evaluation. With a larger sample, there were a few more differences noted. Batch 7, which saw a 10 minute hop stand, was ranked as having the most aroma, most flavor, and least bitterness. This aligns with the IBU testing conducted, but does it tell us that more aroma and flavor compound are retained by doing a shorter rest? It’s certainly possible, but outside the scope of this experiment.

Batch 5, which was boiled for 10 minutes with no hop stand, was ranked as having the least aroma, least flavor, and most bitterness. Batch 9 was ranked a close second in bitterness, and had measured IBUs nearly the same as Batch 5, but did rank better in terms of aroma and flavor.

| Batch | Most Aroma | Least Aroma | Most Flavor | Least Flavor | Most Bitterness | Least Bitterness | ||

| The numbers above represent how the eight tasters voted on specific elements of the beers that were ranked. | ||||||||

| #5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | ||

| #7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| #9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | ||

Conclusion

The results of the experiment ranged from some level of inconclusiveness, to validating and providing perspective on some of what we already knew about the effect on bitterness for post-boil hop additions.

Evaluation of Results

The validating piece of the experiment was that post-boil hop additions do indeed generate significant amounts of bitterness, especially when compared to an aroma addition that is boiled for a short period of time. The level of bittering does seem to accelerate quickly after the hops are added, leveling off over time despite still creating additional bitterness. However, the experiment raised many questions that would require further research to answer.

- Longer hop stands certainly lead to more bittering, but does aroma suffer because of it? The sensory results seem to imply that could be the case, but more intensive testing would be needed to validate that thought.

- Recent research conducted in the Fermentation Science program at Oregon State University has found that bitterness can be caused by more than just iso-alpha acids. Specifically, bitterness can be caused by the existence of hulupones and humulinones in hops being extracted into the wort.6 Are these compounds a significant contributor to bitterness and IBU measurement when hops are added post-boil? Could it be possible to extract bitterness from hops by adding them below the alpha acid isomerization range? Furthermore, would doing so have benefits in retention of aroma and flavor compounds?

Evaluation of Methods

The methods chosen for the experiment were designed to allow for as many batches as possible, while aiming for consistency over them. For the most part, I believe this was achieved, and the consistency of ingredients and methods from batch to batch was sound. However, the direct heating of the kettle in Set 1 did seem to cause a variance in results, and did yield the data inconclusive. Any future testing would be better suited with a different method for maintaining the temperature of the wort.

While the small batch method did allow many batches to be completed in a timely and cost effective manner, further testing would likely be better suited with a lesser number of batches brewed to larger volumes. Because of the very small volume of each batch, any difference in variables was magnified, as was on display in the method of heating used in Set 1. Even an increase in batch size to 3 – 5 gallons would certainly help create consistency in results. By limiting the number of batches tested to five or less, and limiting the volume of each batch to 3–5 gallons, the beers could utilize a base, all-grain mashed wort that could be customized for the experiment.

Lastly, one area that did not receive primary focus was yeast and fermentation. A simple method of pitching dry yeast directly into the fermenter and conducting fermentation at the ambient temperature of the room was used. However, this resulted in a warmer than ideal fermentation temperature, and some yeast off-flavors were noted by a few members of the sensory panel. Ideally, reducing the number of batches, and increasing their size slightly, would allow for a more controlled fermentation environment, including the use of a high viability liquid yeast culture with pitching rates designed specifically for the experiment.

Future Work

As noted, the experiment certainly provided some very useful data on the effect of post-boil hop additions on the bitterness of a beer. However, there were certainly some interesting results that yielded some additional questions. In part because of what was learned from the methods used in the experiment, and in part because of the data collected, a follow up experiment on the effect of bittering over a wider temperature range would likely yield useful data, and help answer some of the questions raised in this experiment. To successfully complete such a follow up experiment, the equipment would likely need to be capable of keeping a highly consistent temperature over a period of 15–30 minutes, and ensure that the temperature was consistent throughout the kettle. An electric brewing system consisting of an electric element for heating, a PID or temperature controller to maintain a consistent wort temperature, a pump for recirculation, and a whirlpool outlet to ensure the wort remained moving, allowing for even temperature distribution, would likely work well for such an experiment. The goal of the follow up work would be to answer the questions posed earlier; what is the effect of a post-boil/whirlpool hop addition on the bitterness of the beer, even below alpha acid isomerization temperatures, and how does this affect hop aroma and flavor?

Acknowledgements

Many people volunteered their time and efforts in helping me complete this project and report. Foremost, David Curtis of Bell’s Brewery played a pivotal role in procuring the resources within Bell’s to help with IBU testing, and in organizing a sensory panel. David’s excellent presentation at the 2014 National Homebrewers Conference entitled “Putting Some Numbers on First Wort and Mash Hop additions” was in part what inspired me to propose this experiment to the AHA. For his efforts in this project, I’m sincerely grateful.

I’d also like to thank Luke Chadwick and the rest of the team at the Bell’s Brewery lab for performing the IBU testing, and answering any follow up questions I had. To the members of the sensory panel from Bell’s who participated in the experiment, many thanks for offering up your time and enthusiasm for that portion of the project.

Stan Hieronymus was also very gracious with his time and willingness to provide advice and resources all the way from when I was writing the proposal for this project through the completion of this report. Stan is one of the most knowledgeable and genuinely nice people in the brewing world today, and I can’t thank him enough for the help he provided.

Last but not least, I’d like to thank Jeff Rankert of the Ann Arbor Brewers Guild, Ryan Hamilton of Pilot Malt House, and Phil Pierce of the Brewsquitos Homebrew Club for reading the initial version of this report and providing invaluable feedback. All are great technical brewing minds, and Phil in particular has repeatedly helped me refine beer writing I’ve done in the past.

Works Cited

- Steele, Mitch. “Hop Bursting: Maximizing Hop Flavor and Aroma.” Zymurgy Magazine, November/December 2013: pages 20 – 26.

- Hall, Michael L., Ph.D. “What’s Your IBU?” Zymurgy Magazine, Special Edition, The Classic Guide to Hops, 1997: pages 54 – 67.

- Mills, Adam. “From Five Gallons to Fifteen Barrels” [PDF document]. Retrieved from American Homebrewers Association Web site: http://www.homebrewersassociation.org/how-to-brew/resources/conference-seminars/

- ASBC Methods of Analysis, Beer-23, Beer Bitterness. Retrieved from http://methods.asbcnet.org/summaries/beer-23.aspx

- J Zainasheff. “Whirlpool/Immersion Chiller”. Retrieved from http://www.mrmalty.com/chiller.php

- Algazzali, Victor A. (2015). The bitterness intensity of oxidized hop acids : humulinones and hulupones (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from: http://www.worldcat.org/title/bitterness-intensity-of-oxidized-hop-acids-humulinones-and-hulupones/oclc/893912673

* * *

Nick Rodammer, member of the Brewsquitos Homebrewing Club, is a homebrewer and AHA member from Michigan.

The post The Effect of Post-Boil/Whirlpool Hop Additions on Bitterness in Beer appeared first on American Homebrewers Association.

An excerpt from Queen of the Turtle Derby and Other Southern Phenomena by Julia Reed

An excerpt from Queen of the Turtle Derby and Other Southern Phenomena by Julia Reed